- Home

- Articles and blog posts

- Theorizing in Qualitative Research (Part II)

Articles and blog posts

Theorizing in Qualitative Research (Part II)

By Huayi Huang

Cite as:

Huang, Huayi (February 2020). Theorising in Qualitative Research (Part 2). https://drkriukow.com/theorizing-in-qualitative-research-part-ii/ DrKriukow.com

In the last post, we challenged the myth that good researchers do not theorise, and directly observe without theory. In giving reason for this challenge, we drew on known facts from the qualitative research literature – documenting some of the competing ideas and ideals of truth, in the academic and wider world.

We also introduced in part 1 the idea of abstract thinking, in terms of sets of academic ideas covering specific areas (‘small’ theories), mid-ranged areas (‘middle-ranged’ theories), and all encompassing areas (‘grand theories) of our lived experience.

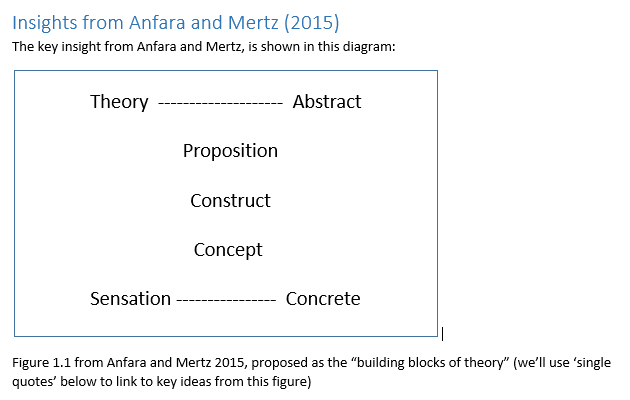

This post introduces and elaborates on an answer to our original question: what does theory mean, in qualitative research? To aid in clarification, we turn to a proposed way of thinking about all of this, from Anfara and Mertz (2015). To illustrate their proposal, we draw on existing knowledge about a middle-range sociological theory of ‘normalisation’ (http://www.normalizationprocess.org/): around changes in social and psychological structure in the implementation of new ideas and practices.

In this way of thinking about theory in qualitative research, we start by reflecting on our daily sensations, key events, and other things we experience as we live our lives. An end point in seeking to learn and understand a theory then…could be

“to travel into someone else’s mind and become able to perceive reality as that person does. To understand a theory is to experience a shift in one’s mental structure and discover a different way of thinking. To understand a theory is to feel some wonder that one never saw before what now seems to have been obvious all along. To understand a theory, one needs to stretch one’s mind to reach the theorist’s meaning.” (Anfara and Mertz 2015, p2)

Back to the world of daily sensations, experiences, and events, then, we develop and name basic ideas for our systems of thinking (‘concepts’ in fig 1.1). In order for this to be possible, the names and vocabulary we use to describe new sensations, experiences, and events, must be meaningful and ‘true’ in some sense that connects with what we already know (and in this way connecting with the sensations, experiences, and events from our past). In the case of our theory of normalisation today then, a basic idea it proposes for our consideration is “relational integration”, aiming to furnish us with a sociological idea for naming and talking about how we seek to build new trust relationships (or sometimes fail to do so), with the new ideas, practices, and people coming into our lives.

Moving up in the level of abstract description, and building on these ‘concepts’/subconstructs then, the inventors of this theory of normalisation, proposes that we cluster the idea of “Relational Integration”, alongside 3 other concepts of “Interactional Workability”, “Skill set Workability”, and “Contextual Integration”, clustered under the general idea of “Collective Action”. This larger unit of sociological thinking about “Collective Action” then, is offered to us as a way to reflect on how we might collectively ‘do’ or make concrete a new set of ideas or practices. For this theory of normalisation, aiming to help us order and structure our reflections on group based enactments of new ideas or practices, by encouraging us to generate and review evidence relevant to this unit of thinking.

Once we are reasonably satisfied that a ‘construct’(see figure 1.1) like “Collective Action” is descriptive of a part of our worldly sensations, experiences, and events (in quantitative terms based on achieving some collective belief in the construct validity of ideas like “Collective Action” and “Relational Integration”), we come to ‘propositions’ which might be offered to others, in sharing the relationships between ideas – as we or our research participants experience in a research study. In everyday terms, ‘propositions’ are simply shareable/writable/readable claims about their reader’s worldly experiences – which somebody else may or may not accept and take onboard (e.g. as part of peer review). As typically written into papers, journals, books, etc. of the scientific literature, these claims bring into explicit relation (e.g. scrutiny by 3rd party colleagues, hypothesis testing, etc.) multiple constructs about the facets of worldly experience making up the target of a scientific theory or communication.

For the theory of normalisation today, its target interest is broadly around significant changes in psychological and social structure, as we may experience in the presence of an intervention into the fabric of our professional lives; our research participants’ shared experiences of such changes in the presence of an intervention then, can be described and explained using its (sociological) vocabulary. Interestingly, as offered through the introductory knowledge of its key ‘constructs’ and their interrelationships on its website (http://www.normalizationprocess.org/what-is-npt/), there is a sense that potential users are invited to take the ideas (e.g. “Relational Integration”) and relationships offered (e.g. “Relational Integration” is always part of “Collective Action” sensations, events, and experiences) the rest of the way…into an interpretation and set of interrelationships that make sense for their own experiences of changes in psychological and social structure, in the presence of an intervention into their lives. In the work of its academic users, further work is of course needed to build on the sociological ideas and relationships offered, in such a way as to more clearly and fully define the key relationships between ideas (‘propositions’), as experienced by the researched or researchers (in working towards academic publication). In doing so, perhaps in illustration of Anfara and Mertz 2015’s early proposition, of ‘stretching one’s mind and abstract perceptions to reach these (sociological) theorists’ meaning by these ideas’.

To our quantitative colleagues, this flexibility in the exact meaning of key theoretical ideas, and the relationships between them can bewilder. To working academic qualitative researchers, this same flexibility and intellectual plasticity is what we live for and are excited to rethink, in light of the new human experiences we discover in a research study. When any of us thinks qualitatively in any case (in terms of key categories in our experiences and key relationships between these), our focus is on the more adaptive and flexible dimensions of human experience, as lived in the day to day. Through keeping the exact meaning of its key ideas and relationships flexible, for a project prior to its data or evidence collection, we allow the lived experiences of our participants to meaningfully inform and reshape the collective content and structure of what it means to be human – as we live through the changing realities and common-senses of our personal and professional ’lifeworlds’ .

Moving forward

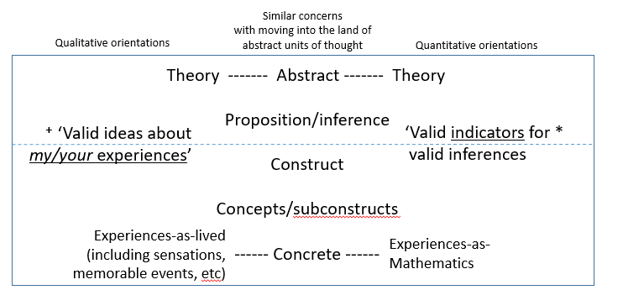

To aid collective synthesis of learning between qualitative and quantitative colleagues, I offer the following adaptation of Anfara and Mertz’s original schematic earlier, in light of what we’ve said. To highlight some of the professional differences in evidenced learning which could be bridged:

Explanatory note

+ Qualitatively, the natural languages we know are invaluable, in flexing the content and structure of our abstract adaptations to a changing experiential world. Qualitatively, we may add to, or discover new realities, in light of proposing inferences on new or known experiences.

* Quantitatively, let us build our house of knowledge far away from the ambiguities of natural language. Quantitatively, data generation based on ‘valid constructs/subconstructs’ and pre-existing associated instrumentation is ‘the reality’ on which we draw inferences for others.

In sharing these and other sets of ideas about coming to know the world into your wider community then, it is crucial that the relationships amongst the ideas and constructs you propose, is ordered in such a way that others can find some:

…relationship with their ideas about their experiences with the target phenomena of your theory (corresponding to the 5 theories of truth mentioned previously).

References

Anfara and Mertz (2015, 2nd Edition, Kindle edition). Theoretical Frameworks in Qualitative Research, ISBN 978-1-4522-8243-5