- Home

- Articles and blog posts

- Living with machines that can tell right from wrong? An introduction to key ideas in ethical reasoning

Articles and blog posts

Living with machines that can tell right from wrong? An introduction to key ideas in ethical reasoning

By Huayi Huang

Cite as:

Huang, Huayi (August 2021). Living with machines that can tell right from wrong? An introduction to key ideas in ethical reasoning. https://drkriukow.com/living-with-machines-that-can-tell-right-from-wrong-an-introduction-to-key-ideas-in-ethical-reasoning/

Introduction

In a previous article, we started exploring the evolution of artificial intelligence ideas in context of the history of modern computer science. Making the distinction between ‘strong variants’, and ‘narrow/weak variants’ in ongoing efforts to replace and mechanise parts of our natural intelligence.

Whilst progress continues in “the theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks normally requiring human intelligence” (in search of ideas and technologies for strong AI), guidelines around ethics involving artificial beings are emerging as a research area of increasing interest.

To help us unpack this emerging debate, lets familiarise ourselves with some foundational ideas others have considered in the past, in building our own framework for reasoning about the ethics of our achievements and actions. In this article we work with the idea of ethics being about finding our own frameworks for judgement for determining right or wrong, and cover some of the key ingredients offered for doing this from the ethics literature of the past. In delving deeper into some key ideas from the (documented) history of ethical thinking, some of these ideas might help us in considering current debates around the artificial beings potentially created through our technological developments.

“Whilst progress continues in “the theory and development of computer systems able to perform tasks normally requiring human intelligence” (in search of ideas and technologies for strong AI), guidelines around ethics involving artificial beings are emerging as a research area of increasing interest.”

1. Key ‘ethical ingredients’ in judging decision making or relationship dynamics between beings

In evaluating and reflecting on how we ought to interact with each other and make decisions about relationships, we might talk about the ethics of utility, rights and responsibilities, virtues, and contracts.

1.1 The ethics of utility (utilitarian ethics)

“The end justifies the means” is an idea familiar to many of us, as we seek to make a positive difference in the world. Starting with the idea of evaluation centered around potential or actual utility, achieving the ‘right outcomes’ is at the heart of which decisions and relationships are considered right or wrong. For example, in engaging the services of professionals from a cheap garage to fix our car at a budget price (the desired end), or doing what we can against ‘wrong outcomes’ in context of a particular time or place, e.g. when healthcare outcomes become unnecessarily unsafe and harmful, rather than healing – as I became aware of during my PhD (on Development of New Methods to Support Systemic Incident Analysis of patient safety incidents).

In moral reasoning around utility, a being tells right from wrong by focusing on the rightness of the anticipated or actual outcomes, rather than their own or others’ conduct leading up to the outcomes. If the priorities of a country is in getting the ‘right amount’ in its aggregate level economic outcome indicators for example, then whether policies of herd immunity or alternative approaches are better for responding to COVID-19 is of secondary and peripheral importance – so long as the aggregate level ‘right amount’ is achieved.

1.2 Which behaviours are ethical?

In evaluating how we ought to behave with each other then, ethicists speak about both duties and rights which govern how we do things, and in reflecting on how we ought to behave in interacting with other beings.

The ethics of duty is the study of deontontology or deontological ethics – in reasoning through the responsibilities we have to ourselves and others. Counterpart to this are the ethics of rights – such as those codified in human right conventions and legislation for example.

In reasoning about a particular duty or right and its associated behaviours, we may focus less on whether the right or wrong outcomes are achieved, or achievable. For example, whether a parent is fulfilling their duty of care towards their child is arguably less of a outcomes-based judgment, than the duty of our water suppliers to fix the water supply when it goes down (at least in the UK). Some of our codified rights – such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) legislation recently in the UK – can also receive more or less media attention at times, than other rights we convinced ourselves to have because we are human beings.

Should artificial being have the human right to favourable conditions of work too? Currently no one really knows!

But in reasoning about the ethics of decision making or relationship dynamics involving other human beings as a means towards some greater goal (e.g. of eradicating world poverty, or to achieve the company bottom line), we do know that the ‘right ends’ do not always justify their means of potential or actual accomplishment.

1.3 Do we have intrinsic virtues as human or artificial beings?

Virtues based ethical frameworks all rest on the assumption that as human beings, we have virtues intrinsically (i.e. from NATURE), or can be taught to become virtuous – in how we relate to, think about, or behave towards other beings we co-exist with. Aiding children to learn to become beings with graces and courtesies (https://www.berkshiremontessori.org/msb-blog/basics-grace-and-courtesy), is one example from ethical principles codified as a core element of Montessori Education – of the right way to interact with fellow beings in the world (ranging from other animals to fellow human beings).

Turning to broader developments in the world of science and scholarship – the advanced academic training of 19th and early 20th century researchers, was in the hope and ideal of producing beings intrinsically competent and trustworthy in their roles in investigations advancing the public rather than private good, and in disseminating the results from (re)examining the human condition. But darker chapters from our more recent history, has led to a general loss of strength of belief in the virtuousness of modern scientists, as evidenced by the burgeoning and complex regulatory landscapes and codes of ethical practice, developed since the 1950s around research involving human participants.

1.4 The contracts we form with each other…

From the perspective of considering the social contracts which we form with each other (contract-based ethics), there are usually both rights and responsibilities in play in the norms, decisions and relationships we make with each other. In personal or private life these rights and responsibilities tend to operate in more tacit, assumed forms – sometimes leading to quite unexpected and bewildering interactions when particular decisions or relationship dynamics unexpectedly upset our loved ones! In professional settings, formalised contractual arrangements often define the legally binding relationships that may be exercised between legal entities – for example in clarifying/defining the ‘rights’ or ‘wrongs’ in a contractual relationship to be expected between a service supplier and the business or home being supplied.

“The injunction for robots to aid human beings in avoiding harm is similar to the tradeoffs typically at the heart of medical trials: where the benefits and harms of new medicinal or technological products are weighed, and considered alongside the ongoing potential of this kind of learning process (the medical trial) to truly advance knowledge on the intervention investigated.”

2. Coexisting with Artificial Beings that care about rights and responsibilities?

Looking forward to our potential relationships with artificial beings then, it is interesting to reflect on how the ethics of utility, rights and responsibilities, virtues, and contracts may translate…

In living with machines which may or may not be ethical, the propositions offered by Asimov’s 3 laws of robotics focus on a future in which utilitarian ethics, rights and responsibilities, hold centre stage in the framework of judgment codified in these laws.

The injunction for robots to aid human beings in avoiding harm is similar to the tradeoffs typically at the heart of medical trials: where the benefits and harms of new medicinal or technological products are weighed, and considered alongside the ongoing potential of this kind of learning process (the medical trial) to truly advance knowledge on the intervention investigated. The second and third of Asimov’s laws are more procedural rather than outcomes-based, where the robot must first prioritise its duty to obey orders from beings who are human, and only then has the right to prioritise its own existence – when this does not conflict with avoiding human harms and following human orders.

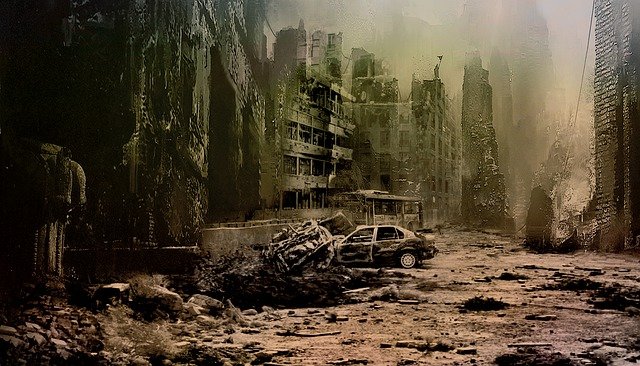

I recently watched a cool show called “The 100” (see https://the100.fandom.com/wiki/A.L.I.E.), where the main AI character A.L.I.E. in essence ignored any consideration of the ethics of rights and responsibilities, in prioritising the mantra supplied to her, of the “the end justifies the means”. Somewhat explosively in a later episode, the writers reveal that A.L.I.E. had previously decided that a public good key to the role defined for her (to identify a solution to a likely future of human extinction due to global overpopulation), was best addressed through actively causing a nuclear apocalypse; in doing so, completing ignoring any responsibility to the wellbeing of those human beings who would be impacted and harmed, by the means by which this ‘public good’ was to be achieved.

A notable warning I guess, for the folly of developing frameworks for judgment focusing only the utilitarian ethics – of the relationships that are right for us to make with human, artificial, or other beings!

3. Looking to the future…

What might an artificial being look like, if they were programmed with the key ideas for ethical reasoning shared in this article?

Please let us know in the comments below!