- Home

- Articles and blog posts

- On observational learning in research

Articles and blog posts

On Observational Learning in Research

By Huayi Huang

huayi.the.researcher@gmail.com

Cite as:

Huang, Huayi (May 2021). On Observational Learning in Research. https://drkriukow.com/elementor-3389/

To participate or to observe, according to Raymond L. Gold

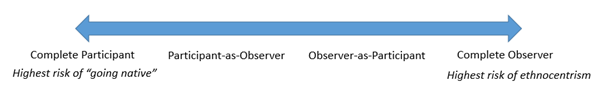

In 1958, a professor of sociology published a landmark paper still influential for field researchers today – around four types of observational roles (Gold 1958, see fig 1 below). His proposal teaches us to treat the relationship between participant and non-participant observations not so much as a dichotomy, but as falling along a spectrum of 4 key types. On the one end, the “complete participant” – totally involved in ‘doing’ the life of the group, and is part of the ‘normal life environment’ of the researched. On the other end of the spectrum – the “complete observer” – who remains aloof and uninvolved in the social setting and tasks of the group (and whose presence may not be necessarily known to those being watched).

The complete participant seeks to adopt the ‘role of the native’ – in the sense of seeking to embrace and appearing to identify with the life of those being observed. In fully engaging with their social life, the notes, recordings, reflections, and documented learning about the observational setting is deprioritised – at least in study participants’ exposure to these field work(er) activities. In essence the sense of ‘self’ of the complete participant, becomes very much part of the normal fabric of study participants’ personal or professional lives.

Like the complete participant the Participant-as-Observer shares the need to be ‘in role’, in their participation in the ‘normal’ life and tasks observed; in contrast to their relationship with the complete participant, study participants are typically aware of the dual roles played by the Participant-as-Observer, and gradually adjusts their expectations and habits accordingly for this slight intrusion into their normal way of life.

To a field worker engaged in this second type of relationship with that which they are observing, it is okay to eg. get out a small, unobtrusive notepad or device to record a few informal reminders. These reminders might be elaborated on later, out of sight – but with broad participant consent and knowledge that their behaviours and interactions are being recorded for research purposes.

Study participants may be part of formal observations also (eg. in seeing an interviewer write down notes during complementary study interviews), and the informal participation by the researcher in the life of the setting or group (eg. office parties) is no longer the only thing in the awareness of the participant. In Participant-as-Observer field work, any dilemmas or tensions in the dual roles of participant-observer are mostly resolved in favour of the demands for participation by the researcher: in playing the part of a novice taxi driver (in transport field studies) for example, or trying to act as an organisational colleague as part of a secondment role (in an organisational study).

The development of longitudinal relationships (such as friendships) still occurs, like in the case of the complete participant, but the relationships between the field worker and his/her friends from the setting must develop to accommodate the additional role of the scientific observer; in this role we are expected to take notes, and balance the ongoing tension in relating sometimes as an ‘insider’ and active informal participant to the particular things, events, and ideas being expressed and experienced, and sometimes as an ‘outside observer’ with a more impartial and critical eye.

In more cross-sectional learning contexts (eg survey like), you might engage with your fieldwork as an Observer-as-Participant, leading with the observation part of this dual role. Like in a survey, the contact between the researcher and the researched is relatively brief, and fragmented with respect to the entity, process, experience(s) etc. being studied. Field researchers working in complete participant or Participant-as-Observer roles have been long concerned with risks of a researcher “going native”[1], which are minimised in the role of Observing-as-a-Participant. Accompanying this benefit however is the limitation of an increased risk of misunderstanding, or more typically under-documentation: of the full complexities, tensions, contexts, coherence, etc. of the individual lives sampled in creating a cross-sectional data set. Whilst quantified ‘instrument validity’ approaches seek to alleviate possible misunderstandings – something like census data for example is far from a nuanced understanding of the full breadth and depth of our individual day to day challenges.

In adopting a complete observer role then, the field researcher again simplifies his life down to 1 primary role, relating to the lives and experiences of co-participants in the knowledge production of a study as just a learner (about these experiences). Unlike the complete participant, the complete observer does not do much…other than focusing on learning through observation.

This complete observer role comes with significant detachment and distance built in – in relation to the phenomena, setting, tasks, groups, etc being studied. But researchers in this role also risk being limited to overly ethnocentric evaluation of other cultures, for example in application of the preconceptions originating in the standards and customs of their own culture – in pre-judging rather than describing things of significance for the study.

[1] Referring to the experience where a researcher uncritically accepts the views they learn from the ‘field’ as their own, because they have become too similar in outlook, worldviews, etc. to their study participants.

“On the one end, the “complete participant” – totally involved in ‘doing’ the life of the group, and is part of the ‘normal life environment’ of the researched. On the other end of the spectrum – the “complete observer” – who remains aloof and uninvolved in the social setting and tasks of the group”

Descriptive or judgemental observations?

As we go through life, we learn to reason in our own ways about the world – based on what we see around us and the experiences we have. Along with the patterns of reasoning we come to know and apply in our learning projects (in our deductive, inductive, abductive, and retroductive inferences), comes our personal curiosities, biases, inclinations around what we (naturally) think is interesting or important, why we think things happen, and a personal sense of what useful or valuable knowledge is (Ravitch and Riggan 2017, p9-10). All these personal interests and habits of thought, is what furnishes us with the intrinsic impulse to know more, know better, know more deeply, etc.

But when it comes to trying to describe what we see, for others, we try to set aside as best as we can our preconceptions about what is significant. In particular, setting aside the deductive, inductive, abductive, or retroductive patterns familiar to our reasoning minds – to ‘bracket out’ our biases, assumptions, personal theories, previous experiences, or presuppositions about the things that exist in the world.

We engage in deduction, induction, abduction, or retroduction later on in the scientific process – particular as we come to analyse the research data we are creating through observations, in and of the field and sites of study. The idea of ‘bracketing out’ (Given 2008) the more abstract ideas we see the world through, is intended to support us in a process of suspension of judgement – as we seek to describe the phenomena we are studying.

In observing the development of children in a study for example, we may naturally make judgements such as “they jumped on the steps really well, much better than yesterday”. But seeing the value of this kind of statement from the perspective of another colleague, teacher, etc. highlights that we may or may not readily agree on this being a valid judgement for what we actually saw.

Of much greater benefit, is an alternative such as “they jumped 1 metre from the steps, and landed feet together rather than apart; after landing they took a bow!” This kind of observational statement requires a reader to only take on trust our descriptions of what we saw, rather than also our evaluation or judgements (eg “their jumping/landing today was much better than yesterday”).As such, increasing the value of the observational statements recorded to be helpful – to a broader range of learning and inferential purposes. As I highlighted in a book chapter earlier (Sujan, Huang & Biggerstaff 2019), it can be useful to consider trust as an attribute of interpersonal relationships. So in the context of building trusting interpersonal relationships with your informants, perhaps little of this relationship actually ends up in the observational data. But this kind of relationship building is nevertheless important, since it enables your study participants to feel (psychologically) safe in assuming that you will give them the benefit of the doubt, in choosing to continue to share their normal thoughts and actions even in your presence. Making a strong distinction between the descriptive and analytical/inferential parts of the scientific process can also enable some types of readers to trust, as they give you the benefit of the doubt for those inferences made which they do not entirely follow or endorse.

“relationship building is nevertheless important, since it enables your study participants to feel (psychologically) safe in assuming that you will give them the benefit of the doubt, in choosing to continue to share their normal thoughts and actions even in your presence”

Indirect and direct observations

The most common type of observations we do in learning about life, is indirect observations. This type of observation is characterised by the fact that we are usually engaged in some other activity – distinct from the act of observing.

For example, we might be taking a walk in the park, and spontaneously observe something of interest about the new health equipment available for use by local residents. Our observational-attention is typically diverted from our original activity (eg. of walking in the park), or distributed across multiple ongoing activities (eg as a head chef manages a whole kitchen during service).

In contrast, direct observations are characterised by an exclusive focus on that which is being observed. For example, as I sat down in a room to observe the proceedings of Scottish GP cluster meetings (Huang et al. 2021), as part of learning about ongoing collaborative improvements to the primary care we receive as patients. More generally, seeking to directly ‘follow the thing’ of interest (eg. an entity, process, phenomenon, experiences, thread of reasoning offered by our participants, etc) – as best as we can whilst suspending our judgement of this thing we are following in our direct observations.

Three final points

In updating some of Gold (1958)’s other propositions for current times, it is worth revisiting:

- The idea that the field researcher may benefit from reflecting on which role(s) they wish to adopt in a study (fig 1), and in how they might then facilitate their respondents and participants to play the corresponding roles entailed by this choice. For example if the field researcher has a professional background in the ‘normal’ life and tasks being observed, but wishes to engage in an Observer-as-Participant relationship with the field of study, it may help to particularly highlight the ‘outsider’ and research-specific reasons of the roles they take on, and work to suppress expectations on you to taking part in the group activities, and in the opportunities for social interaction with the group. Over time this will enable in your participants a sense of distance and detachment also – between your research role and their own roles.

- Regarding Gold’s point around the sense of ‘self’ being always involved in field studies, the corollary is that one’s internal standards of behaviour, morals, etc. is always involved in field studies. As a complete participant this is relatively clear – in aligning my internal standards to that of an ‘insider’ (of the setting), taking time out occasionally to reflect on what I learn. As a complete observer my role in a study is also relatively clear – my internal standards in a research role differs enough…from the often undocumented doing or thinking of my study participants.

- The tension between becoming a part of what you study, or being apart from what you study is the territory of the Participant-as-Observer, and Observer-as-Participant; role conflicts may emerge here relating to the tension between ‘doer’(participant) and learner(observer). Their solutions will be inevitably worked out in the practicalities of the specific observation/participant situations that unfold, where you sometimes choose for the doing to take precedence over your reflective learning, and sometimes vice-versa. All of this leading to the familiar challenge of the field researcher – in coming to a firmer sense of “who am I” in the learning created in interaction with their field settings.

References

Given, L. M. (Ed.). (2008). BRACKETING entry, in The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage publications.

Gold, R. L. (1958). Roles in Sociological Field Observations. Social Forces 36(3), 217-223.

Huang, H., Jefferson, E., Gotink, M., Sinclair, C., Mercer, S., & Guthrie, B. (2021). Collaborative improvement in Scottish GP clusters after the Quality and Outcomes Framework: a qualitative study. British Journal of General Practice. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2020.1101

Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. (2017). Reason & rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research (2nd edition). Sage Publications.

Sujan, M. A., Huang, H., & Biggerstaff, D. (2019). Trust and psychological safety as facilitators of resilient health care. Working Across Boundaries: Resilient Health Care, Volume 5, 125.