Analysing Focus Group data

Focus Groups

Focus groups are essentially a “series of discussions to obtain perceptions on a defined area of interest” (Krueger and Casey, 2009: 2). Typically, these seemingly informal discussions occur in a group of no more than 12 individuals (Asbury, 1995; Smithson, 2008), who share some common characteristics (Franz, 2011) and “have a direct experience of the topic” (Acocella, 2012: 1127), and, thus, are treated as ‘experts’ (Stewart and Shamdasani, 1990). These discussions are facilitated by a moderator.

Analysing focus group data

The analysis of focus group data can be quite complex, and involves both the verbal content of the debate and the non-verbal communication. Still, focus group data are often under-analysed and used, for example, to simply report emerging themes and coding frequency. When preparing this post, I did a quick online search for what people say about focus group analysis and immediately found comments such as the following:

“analyzing focus group interviews is not greatly different from analyzing one-person interviews.”

“I personally think that the analysis of focus group data is not much different from the analysis of any other kind of interview data. Most people who ask for specific analytic tools in focus groups do so because they don’t have experience with analyzing other kinds of qualitative data, so they think there must be something unique about focus groups.”

…

Needless to say, they couldn’t be more wrong. Focusing exclusively on individual participants’ accounts (which would be the case if “the analysis of focus group data [was] not much different from the analysis of any other kind of interview data”, as suggested above) would mean that we are overlooking the most unique and valuable aspects of focus group discussion – the group’s views and group dynamics.

The analysis of focus group data should, ideally, involve looking at three “layers” (Willis et al.) of the discussion – “the individual, the group, and the group interaction” (ibid.).

Importantly, these different layers are not necessarily “steps” – thus, in practice, the analysis of one layer is difficult to separate from another (although I think there are also some guidelines that suggest doing so). When you investigate the “individual” layer, for example, not only do you want to pay attention to all views and opinions expressed by one group member throughout the discussion, but also to how this participant “functioned” within the group (were these views relevant to what was being discussed, were they similar to/conflicting with the group’s views, etc.), to whether these views changed throughout the discussion (were they influenced by the discussion? Did they emerge because of some other participant’s views?), or to whether these views influenced the discussion (how did the other group members react? Were these views supported? Or ignored? Was the participant silenced?). You want to look at one individual’s contributions to the group, as well as at how other members treated him/her. You may also see if this person tried to reinforce his/her opinion more than once and, again, how the group reacted.

Similarly, when you focus on the “group” and the “group interaction” layers, it is not possible to ignore the individual roles. When you look at whether the group achieved a “common ground”, or a kind of a shared identity or self-positioning, you need to pay attention to how the individuals constructed this identity together and how each participant responded to the construction of this identity (did he/she contribute to it, and self-positioned him/herself as a group member? Did he/she distance him/herself from the group?).

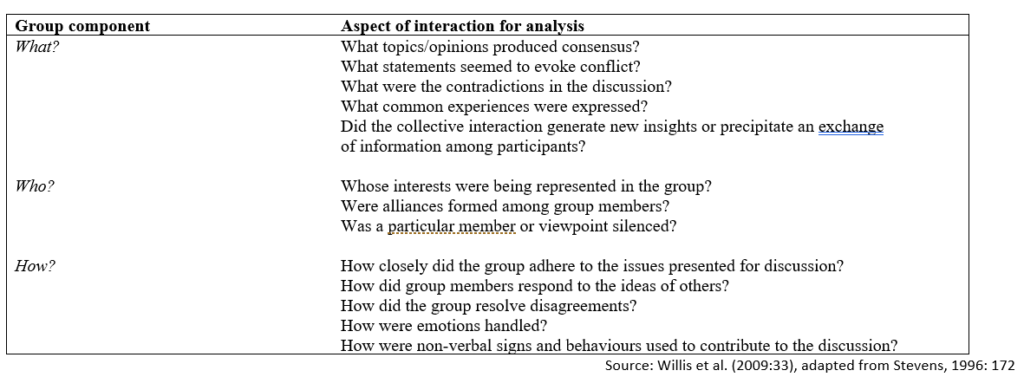

When analysing focus group data, you may use the following checklist to generate some ideas about what to pay attention to:

Onwuegbuzie et al. (2009) propose another useful structure for focus group analysis which is centred around a combination of different data analysis techniques – constant comparison method (which may involve comparing themes emerging in different focus groups), content analysis (e.g. coding the content of the discussion and paying attention to coding frequencies), and keywords-in-context and discourse analysis, both of which involve careful examination of the use of words, and language as a whole, throughout the focus group discussion (at both the group and individual levels).

I would not even want to try to discuss focus group analysis in much detail in such a short blog post, but I do hope that the above gives you a general idea of what it may involve (and that you will understand that it is definitely NOT the same as individual interview analysis!).

Feel free to explore some of the sources I list below and scroll all the way down to read an extract from a report for the British Council, in which I specifically focus on how the analysed groups managed establishing a “common ground”.

REFERENCES

Acocella, I. (2012). The focus groups in social research: advantages and disadvantages. Quality & Quantity. 46 (4), 1125-1136.

Asbury, J.-E. (1995). Overview of Focus Group Research. Qualitative Health Research. 5 (4), 414-420.

Franz, N.K. (2011). The unfocused focus group: benefit or bane? Qualitative Report, 16 (5), 1380-1388.

Krueger, R., & Casey, M. (2009). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. 4th Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Onwuegbuzie, A., Dickinson, W.B., Leech, N.L. & Zoran, A.G. (2009). A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Group Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8 (3), 1-21.

Smithson, J. (2008). Focus groups. In Denzin, N. and Lincoln, Y. (eds.) Handbook of

Qualitative Research. 2nd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Stewart, D.W. & Shamdasani, P.N. (1990). Focus Group. Theory and Practice. Newbury Park: Sage.

Willis, K., Green, J., Daly, J., Williamson, L. & Bandyopadhyay, M. (2008). Perils and possibilities: achieving best evidence from focus groups in public health research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 33, 131-6.

Extract from my focus group results section in Galloway, Kriukow and Numajiri (2017: 29)

“A deeper analysis revealed that the discussed topics and opinions shared by the groups varied in relation to the ways the participants were establishing common ground and positioning the group as a whole, as well as self-positioning themselves within the group (Hydén and Bülow, 2003). For example, in the Hubei focus group, where all the participants majored in English education, they established a collective voice of ‘English majors’ quite effortlessly, and constructed their narratives as a group of ‘experts’ in their field. They spoke of themselves as collective ‘majors in English education’ on one hand, and talked about other students as ‘them’ or ‘other students’ on the other (see Appendix A for an extract). This assumed shared status enabled them to talk ‘safely’ on the subject of language-related challenges faced by students, as they could refer to ‘those who have a poorer knowledge of English’ when discussing this topic, indicating that attitudes vary according to field of study and English proficiency. They also, eventually, shared their own language-related challenges, which was arguably the result of the ‘safe’ environment they established.

On the other hand, this shared status seemed to result in some group members’ opinions being silenced or ignored (see Appendix B for an extract), arguably because of the participants’ evaluation of what is socially desirable and acceptable in their circumstances. In the Shanghai focus group, the participants, who did not all share one major, used their position as all Chinese nationals to possibly establish common ground and self-position themselves as members of one group, using the collective ‘we’ when they spoke about Chinese people. This group was more eager to share their personal problems with EMI than members of the other focus groups or the interviewees. However, in the Sophia focus group, the participants did not seem to have established a shared identity or status from which they could speak in a collective voice. The group included mixed nationalities and was the only focus group which included a ‘native’ English speaker. In fact, one of two ‘native’ English speakers’ position as an expert was determined at the very start of the discussion and this, in addition to his background as a relatively experienced teacher, possibly heightened this ‘expert’ position. He attempted to encourage and lead the discussion. Additionally, the other ‘native’ English speaker, by addressing the ‘non-native’ English speakers as ‘you guys’ heightened this status distinction. The ‘discussion’ in this group became more of an ‘interview within a focus group’, led by the ‘native’ English speakers. This was the only group that did not discuss language-related challenges and they were more critical of using languages other than English in EMI classes.”