Understanding more about patterns of scientific inference (Part II - Induction)

By Huayi Huang

Induction

In Part I of this series we introduced the idea of inference, to refer to the known broad ways in which scientific learning about abstract ideas has been shared in the past, from limited evidence about these ideas. In this second article, we dig deeper into the idea of Induction, when trying to make sense of our social and human worlds.

If you are reading this article, then no doubt you’ve engaged in the human project of trying to generalize from our current and past experiences, so as to interact with things and people around us with some certainty. Quantitative colleagues prefer to address generalizations from specifics through the idea of variables, but some qualitative colleagues find quantified ideas (eg. variables, uncertainty in terms of confidence intervals) rather sterile and distant from the blooming confusion of social and human lives – as lived and experienced in the everyday.

Regardless, the idea of using current/past experience to generalize with some certainty about the future, is commonly referred to as induction in contemporary science and scholarship. Whilst deduction is arguably oldest in terms of recorded Western thought, our ancestors are likely to have been generalising on the basis of experience long before Western thinkers such as Aristotle got recorded!

Two features help us understand the idea of induction…

Feature 1: In moving from concrete specifics to generalities…

The first feature of induction is in the inferential move from the specific -> more general. In the syllogism example from last time, Tom might come to believe that he is living on a round planet from being told by his mum for example [fact 1].

Later on, he might come to learn that the earth we share has ‘people’ living in it (including Tom), perhaps from what he remembers of a geography class at school for example. [fact 2]

Finally, the inductive reasoning step in the example from Tom then, comes in his moment of realisation in inferring based on facts 1+2: that the earth might just be a round planet? Notably, in (inductively) creating this new general idea of his own – about ‘the earth’, ‘roundness’, ‘planets’, etc. – from the limited knowledge shared from Mum and school.

Learning about general ideas of ‘the earth’, ‘roundness’, ‘planets’, etc. are all based on limited, specific evidence here, in the sense that our principal thoughts about the general ideas we live by usually form, based on partial rather than truly comprehensive experience (of these ideas).

Let’s stick to just the physical features of our earth for example, for simplicity. Even if you are the most avid traveller/have read all sorts of interesting books on top of your globetrotting, it is arguably impossible for even a whole community of knowers to have truly directly experienced all parts of our wonderful planet – there’s the experience of the deep sea, high mountains, etc. and when you’ve covered all of those one might quite seriously argue that you haven’t yet stepped far into the past, or will die and miss out on the earth reaching the end of its natural life in the cosmos!

Many major ideas we use to organise how we think about the world, are also abstract, in the sense that they are areas of human experience less clearly/concretely delineated in their own terms. ‘Operationalization’ approaches from the natural sciences try to meet the challenge of concrete delineation of human experience, by defining ideas in terms of referents from our physical reality. This ties abstract ideas down to observables readily accessible through our five (physical) senses. But a great unresolved question in this space is whether all that truly matters in our social and human lives is adequately covered, by approaching our social/human reality only in terms of physical, concrete, unambiguously delineated things?

Feature 2: Accompanying uncertainties in wondering about the wider relevance of inductive ideas

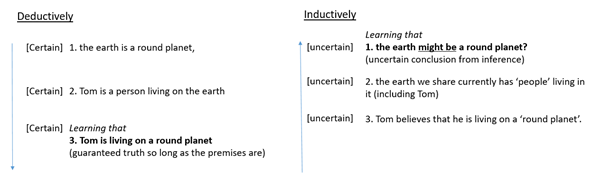

The second feature of inductive inferences is in their increased uncertainty, as the reasoning proceeds on the basis of the available facts. In the figure below around the 3 illustrative ‘facts’ of the earth being round, people living on earth, and Tom being one of these people.

In the deductive line of inference (Fig 1, LHS), we reason with certainty so long as we continue to believe the ‘premises’ within the system of evidence and thoughts to be certain. For example in fig 1 (LHS), the certainty of point 3 depends on the certainty of both points 1 and 2 – as the 2 premises in inference here.

Inductively (Fig 1, RHS), in working through the same facts, we pay more attention to the uncertainties residing within each claim. Drawing attention for instance to the fact that Tom living on the planet is not a fact which will remain forever (point 3, eg when Tom dies), the fact that people currently living on Earth is no guarantee of the ecological future of our species on this blue planet (point 2), and Tom making the inductive inference that the Earth may/may not remain basically round (at least in his lifetime) based on the arguably partial evidence shared through the opinions from Mum and school?

Is it important to emphasis that the 3 facts in question here haven’t really fundamentally changed, as we consider them in terms of Deduction or Induction. What has changed, is in the certainty of knowledge we’re reading each fact with in context of its community of knowers, as well as distinctly different dependencies and lines of thinking around the 3 facts.

In the deductive case, a community of knowers proceed to develop new thoughts based on those already accepted as certain – ie. facts 1 and 2 in LHS of figure 1 (even if those accepted thoughts are clearly disputable from a more inductive vantage point).

In the inductive case the community of knowers has no particular strong predisposition towards any of 3 facts here, holding all three in a state of plausibility (but not certainty). This distinction between plausibility and certainty of knowledge is at the heart of the literature on the “problem of induction”, associated with any inductive inference you make. Without getting into fine details here, the headline idea of the problem of induction is that when you really think about it, many of the regularities we currently live by, and our ideas when we think about these regularities – have no guarantee to remain such forever (as in the 3 regularities from Tom’s example above).

In light of our ever changing and technologized social and human realities, a notable thought to bear in mind!

A secret of the human sciences is in the fact that much of their core subject matter (eg. people’s ideas, experiences, views, everyday lives, social relationships, social structures, etc.) tend to come across as less ‘regular and orderly’ than those typical of the natural sciences (eg biological, chemical, physical mechanisms), leading to experts to comment that:

“Within the natural sciences, induction has led to many theories that appear to operate in many settings (e.g., the laws of physics or of chemical reaction). However, in the social sciences, the numerous factors that may affect phenomena, the role of reflexive subjectivity in determining many processes, and the dependency on context all mean that theories might not survive translation into settings other than those where they were initially developed.”

(The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (2008), Induction)

It’s worth note 2 major interpretations here, of what it means for theories to suffer from problems in translation into other settings. From the idea of reality being a singular thing accessible equally to all, we might argue that this means the theory is proven wrong. From the idea of reality being more of a pluralistic thing depending on your point of view, why should we expect theories of social and human reality to be widely applicable to all social orders and human lives?

In Practice

In practice, researchers often need to support the ideas they develop, with additional evidence to improve the scope of relevance for their ideas. This plays out particularly prominently in published academic qualitative research, due to its tendency towards depth rather than breadth (eg when compared with a solely variable based approach to data and inference).

Ways to do this include:

- bringing in additional supporting probabilistic, statistical data or analyses, as further ‘proof’ of the truth of your ideas (‘truth’ here really referring to the breadth of empirical-applicability of your current ideas – as ‘tested’ in a biological experiment for example)

- through claims to have constructed a representative sample of your population (such methodological-claims commonly appear in knowledge communities with a strong background in statistical thinking, but intermediate/low levels of engagement with existing bodies of qualitative research scholarship)

- Triangulation:

- with supporting evidence from other methods of researching your topic (triangulation of methods),

- theories through which to view your topic (theory triangulation)

- other learners sharing learning on the same topic (investigator triangulation)

- other sources/types of data on your topic, from previous research/knowledge/social and human experiences (triangulation of data sources)

4. or by analogy with similar generalizations, through using the partial similarities from a coherent body of ideas already well established in a community of knowers, to explain/clarify/make sense of a phenomenon. From patient safety research for example, a clear example is in explaining patient safety accident-phenomena, through their partial similarities to what we are already familiar with in some structural features of ‘holey Swiss Cheese’

Further thoughts

In the inductive spirit of the current discussion, this post has hopefully provided food for thought, around how inductive inference proceeds on the basis of limited, specific evidence for your abstract ideas about the world. Knowledge shared is in practice often limited to a particular point of view and set of life experiences, but hopefully make sense in light of your own. Through considering our views together, the hope is that we come away with mutually enriching and shared understanding, of some theoretical and practical issues in doing induction.

For further knowledge on Grounded Theory and inductive development of theories using this qualitative research approach, you can watch the following video on some Core Elements and Common Myths of grounded theory: