Understanding more about patterns of scientific inference (Part I - Deduction)

By Huayi Huang

In being curious of our social and human worlds, the scientist

seeks to learn new things from diverse sources of evidence, ideas, and beliefs.

For the qualitative researcher for example, personal interviews are a common

source of evidence – on the categorical ideas and beliefs we hold. In

quantitative learning interval and ratio data is often preferred, enabling

application of mathematical ideas and beliefs to quantitative kinds of evidence.

Regardless of your disciplinary education and affiliation,

questions of inference come up commonly

in practice. Let’s think about inference here,

as the known broad ways in which we’ve learnt about abstract ideas in the past,

from limited evidence about these ideas. We review Deduction, Induction,

Abduction, and Retroduction as 4 forms of inference from scientific history, in

a series of blog articles, the first of which is the following post devoted to

Deduction.

Deduction

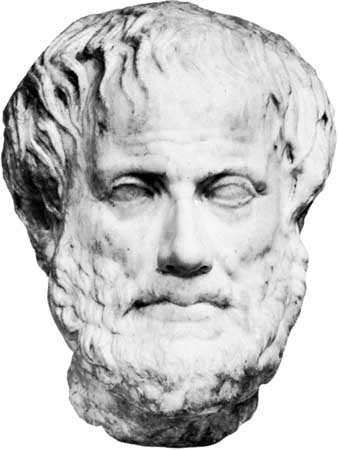

Let us start with Deduction. Arguably the oldest form of inference (at least in terms of recorded Western thought), deduction is exemplified by Aristotle’s ideas around syllogisms – as a sort of codified set of general rules for logical reasoning.

The basic logic of the Aristotelian approach is to start with a set of premises accepted as true by a community of knowers (eg the idea that the earth is a round planet, alongside the idea that Tom is a person living on the earth) and learn implications(e.g. Tom is living on a round planet) guaranteed to be true so long as the premises were. This idea of truth and its discovery hung around for centuries as the main type of ‘valid’ inference, until further studies of logic and reasoning occurred during medieval times.

In aligning with the experience and values of modern industrial society, references to the so called ‘scientific method’ often connects with ideas of hypothetico-deductive methods of inference, rather than purely deductive methods. The hypothetico part represents an expansion of the original scope of deductive inference – based only on premises regarded as true – into hypothetical realms where learners start from premises which are only most likely true – eg in developing specific quantified hypotheses based on some most likely premises sourced from the existing literature.

Assuming these hypothetical truths/premises to be true(at least for the initial parts of a study), deductive inferences can then be made by assuming the truth of these most likely ideas. In context of a literature review, the many previously published premises provide a rich range of premises, analogous to the roles played by the ideas that the earth is a round planet, and that Tom is a person living on the earth, in the example of deductive inference given at the beginning of this section.

In practice, an idea documented in existing literature can be evaluated quite differently by different knowledge communities. For example – continued controversy between academic knowledge communities regarding the idea of reality being a singular thing accessible equally to all, or more of a pluralistic thing depending on your point of view. Suffice to say that there is credible scientific literature/argumentation/evidence on both sides of this debate, with qualitative researchers tending more commonly towards the idea of reality being more of a pluralistic thing depending on your point of view (eg. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794110366802 2010).

From a knowledge community which assume that reality is a singular thing accessible to all, we have the following idealisation, of the method of hypothetico-deductive inferences from experimental biology (Fig 1a). When zooming out beyond the context of individual studies conducted in a manner like in fig 1, the cyclical aspect of the hypothetico-deductive model of inference becomes clearer.

Fig 1: An example of a single hypothetico-deductive cycle, in context of biological primary research (adapted from a biology textbook). Fig 1b presents a reading of these idealisations of experimental design/procedure, from a qualitative research perspective.

In trying to translate the logic of hypothetico-deductivist thinking, into the context of qualitative research, a number of key points are highlighted regarding these 2 topics:

A. In making hypothetico-deductive inferences, the learner is committed to the binary categorisation of all statements about the world as ultimately True or False (Step 7a/b). Research of the ‘predictive truth testing’ types (steps 5/6) benefit enormously from the application of mathematic ideas in learning, experimental rather than naturalistic research designs, and the idea of talking about most likely ideas from the past as only those that are True and those that are False (‘correct’ and incorrect’ respectively in light of your data as in fig 1).

B. In using mathematical language – we benefit from the standardisation and clarity of meaning of its key ideas, eg in regard to what the idea of an average means exactly. These standardising and clarifying effects carry through into communications of what we learnt – in sharing experiences with each other using mathematical ideas. However, note the often unarticulated+unexamined premise (ie. a hypothetical truth/premise) underpinning the act of quantifying social and human reality: that all that truly matters in our social and human lives are expressible through mathematical language and ideas!

C. In preferring experimental rather than naturalistic approaches to learning, we limit the evidence for our shared learning to the closed, highly controlled conditions possible in a lab-like study. Our social and human worlds – and the evidence of these worlds as we experience them in the day to day – usually take place in far more open and dynamic conditions. One role of a qualitative researcher is in trying to make sense of ideas arising from our social and human experiences, whatever and wherever these experiences may be. Following this thought through, it seems almost a misnomer to eg pose the question of whether the ideas shared by our interviewees are true or false(fig 1b).

“ Arguably the oldest form of inference (at least in terms of recorded Western thought), deduction is exemplified by Aristotle’s ideas around syllogisms – as a sort of codified set of general rules for logical reasoning”

Turning to the next implication in fig 1b, we come to the common practice of choosing amongst a set of predefined, quantified possible answers typical of hypothetico-deductivist research. Returning to our opening idea of being curious of our social and human worlds, it is strange to believe in the premise that the key ideas from our social and human experiences can be predicted with any degree of certainty – as shared/recorded through qualitative interviews or observations for example. Outside of the comparatively closed and controlled conditions of formal education, the development of the key ideas we live by, in organising our lives, is typically highly diverse particularly at the individual level (ie it is perfectly natural and okay to think differently from others). Hypothetico-deductivist inferences are usually able to engage in meaningful predictions, only by examining our social and human lives at a group or more aggregated level, ideally glossing over much of the idiosyncrasies making our individual lives meaningful.

Regarding authoritative ideas and their possible distortions on our view of the world, many of us live within a highly quantified knowledge culture. Performance metrics/indicators/data analytics/etc dominate our professional lives. A new gospel of contemporary times is in the authority of mathematics – in the premise that only mathematised ideas really matters, despite our personal knowledge to the contrary.

In Conclusion

In delving deeper into original ideas of Deduction, and expansion of these ideas into hypothetico-deductive methods of scientific inference, we arrive at the thought that hypothetico-deductive inferences in their quantified-experimental forms – are incongruent with the focus of qualitative research on our everyday social+human lives. In Part II of this series, we will turn to Inductive inferences, as a more typically seen pattern of inference seen in qualitative research practices.